Earthshine tonight: How to see May's spectacular Moon event

Lifting the veil on the Moon’s eery glow: here’s when and how to see lunar Earthlight this May.

You may have noticed the Moon exhibiting a ghostly glow lately, where a subtle light is illuminating the usually unlit portion of the lunar surface. This is a phenomenon called Earthshine, and it can be a spectacular sight, not to mention a great opportunity for lunar photography.

In this article, we explain when you can see this lunar glow, what causes it, and why it’s named after one of the most celebrated polymaths of all time.

You can also make the most of clear nights this year with our full Moon UK calendar and astronomy for beginners guide.

When can I see Earthshine?

Weather permitting, you can see Earthshine this evening, 22 May, after sunset (8:56pm BST in London, 8:13pm EDT in New York City).

Earthshine is visible in the mornings a few days before the new Moon, and in the evenings a few days after the new Moon. You might have already glimpsed it before sunrise on 17 May during the waning crescent phase, but if you didn’t fancy dragging yourself out of bed at that hour, we have another chance during the waxing crescent Moon phase.

Here are the next opportunities to see Earthshine:

- 21 May: 3.9 per cent illuminated waxing crescent Moon

- 22 May: 8.9 per cent illuminated waxing crescent Moon

- 23 May: 15.5 per cent illuminated waxing crescent Moon

"Take a look on the evening of the 23 May, and you will be able to see the crescent Moon between the bright planet Venus & the star Pollux, with the red planet Mars just to the left of the pair," advises Dr Darren Baskill, astronomy lecturer at the University of Sussex.

The phenomenon is most visible during the waxing or waning crescent phase, because the illuminated portion of the Moon is slimmer, allowing for a larger portion of the darkened Moon to be illuminated by Earthshine.

It’s the ideal time of year to view, as during the spring, the northern hemisphere is tilted towards the Sun, while at higher latitudes, lingering winter snow and ice still provide ground cover. Snow and ice reflect more light than darker-coloured vegetation and water (i.e., snow and ice have a higher albedo), so we get more apparent Earthshine.

While you might expect therefore, that Earthshine would be brighter during the winter months when snow and ice cover is prolific, the amount of light reaching the Arctic is significantly less, so Earthshine is not as eventful during the winter.

Bottom line: get out and see it while you can!

What exactly is Earthshine?

Earthshine appears as a soft, subtle glow on the unlit, or ‘night’ portion of the Moon during specific phases. This is when a delicate, but somehow ghostly, shape of the full Moon is nestled in the arc of the bright crescent Moon, and it’s a beautiful sight for these early summer nights.

More like this

Also known as the Da Vinci glow, the intensity of Earthshine can vary depending on certain factors, such as atmospheric conditions, Earth's reflectiveness, and the observer's location.

Just be aware of popular media saying that the ‘dark side of the Moon is visible’ as this is incorrect; the dark side of the Moon faces away from us.

As the Moon is tidally locked, we’ll never be able to see the dark side of the Moon from our vantage point here on Earth. Rather, we can see the unlit portion.

What causes it?

Earthshine is also known as the Da Vinci glow, ashen glow, or rather romantically, ‘the old Moon in the new Moon’s arms’. It’s caused by sunlight reflecting off the Earth's surface and then being reflected back onto the Moon.

"Like all planets and moons, the Earth does not emit light – it just reflects sunlight," explains Baskill.

"This reflected sunlight can be seen lighting up the darker part of the Moon for a few days on either side of a new Moon, when the Moon appears as a crescent in the evening or morning sky.

"The Moon’s crescent is caused by bright sunshine directly lighting up the Moon, while the darker part of the Moon is faintly illuminated by Earthshine – sunlight that has reflected off the Earth to gently illuminate the Moon."

Earthshine occurs during the phase in the lunar cycle when only a thin crescent of the Moon is illuminated by direct sunlight – either in the waxing or waning phase.

As for the portion of the Moon not lit by direct sunlight, this is the part we see as the ghostly glow. As we all know, light from the Sun reaches the Earth and illuminates its surface. But this isn’t restricted to land masses, as it also includes clouds, oceans, and the atmosphere.

Some of this light is then scattered, diffused, and reflected back into space. A portion of this reflected light travels towards the Moon, landing on its unlit portion, the lunar night side.

The Moon, despite having a non-reflective surface, bounces back this reflected sunlight from Earth. And it’s this phenomenon, that results in a faint glow on the Moon's unlit portion, providing a subtle illumination to the otherwise dimly lit lunar surface.

What affects it?

The appearance and intensity of Earthshine are influenced by several factors, including the Earth's cloud cover, the composition of its atmosphere, and the angle of sunlight reflecting off our planet onto the Moon. These factors can cause slight variations in the brightness and colour of the Earthshine, making it different each time.

Earth's atmosphere, for example, plays a crucial role in shaping the appearance of Earthshine. As light from the Sun passes through the atmosphere, it undergoes scattering and absorption, with different wavelengths being affected to varying degrees. This atmospheric filtering influences the colour and intensity of the Earthshine, and it’s this light that is ultimately reflected back to the Moon.

Different ground cover will reflect different amounts of light; for example, land reflects around 10-25 per cent, while clouds reflect around 50 per cent of light.

Why is it called the Da Vinci glow?

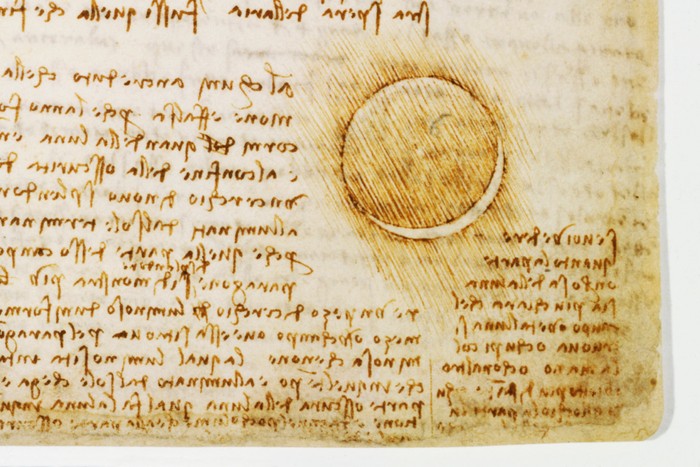

In the early 16th Century, Renaissance polymath Leonardo da Vinci turned his thoughts to unravelling the enigma of this strange, otherworldly glow. He made detailed drawings and sketches of the Moon, and while da Vinci did not coin the term himself, these observations led to its association with his name.

His notebooks contained a drawing that depicts Earthshine, which is now celebrated in the Codex Leicester, a compilation of Da Vinci's scientific writings. Though you’ll need patience if you want to read the manuscript yourself, as da Vinci recorded his observations in his characteristic mirror writing; back-to-front Italian.

What equipment do I need to see the Da Vinci glow?

Aside from the ever-constant wish for clear skies, no special equipment is required. If you have some to hand, while not necessary, using binoculars or a telescope can help you pick out features you wouldn’t ordinarily be able to see on the Moon's surface, and observe the subtle variations in brightness more closely.

You might even like to try sketching the Moon on dark paper with chalk, pastels, or pencils.

Will climate change affect our ability to see it?

Potentially. Researchers looking at Earth’s albedo have found that warming temperatures may result in less intense Earthshine.

As the oceans warmed, they found that fewer low clouds formed over the eastern Pacific Ocean, west of the Big Bear Solar Observatory in California where they were taking measurements. This reduction in cloud cover led to a slight decline in Earth's albedo (reflectiveness), subsequently affecting the intensity of the Da Vinci glow.

About our expert

Dr Darren Baskill is an outreach officer and lecturer in the department of physics and astronomy at the University of Sussex. He previously lectured at the Royal Observatory Greenwich, where he also initiated the annual Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition.

Read more:

Authors

Sponsored Deals

May Half Price Sale

- Save up to 52% when you subscribe to BBC Science Focus Magazine.

- Risk - free offer! Cancel at any time when you subscribe via Direct Debit.

- FREE UK delivery.

- Stay up to date with the latest developments in the worlds of science and technology.