Astrology’s biggest 2023 claim debunked: Saturn isn’t moving into Pisces. It’s not even close

The news is awash with news that Saturn is moving into Pisces, after spending two-and-a-half years in the constellation Aquarius.

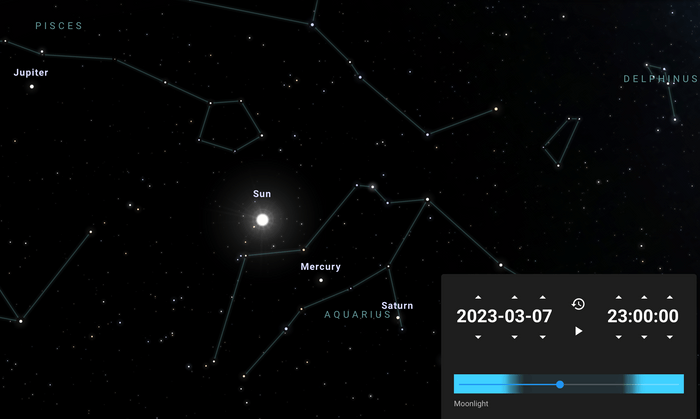

You’ve probably noticed a great deal of hubbub surrounding the ringed planet, Saturn, as it supposedly transits into its new home; Pisces. On 7 March 2023, popular outlets say that Saturn is moving from the constellation Aquarius, where it’s spent the last 2.5 years, into Pisces, where it will remain until February 2026.

The planet Saturn, a cosmic authority which traditionally represents discipline, structure, and responsibility, moving into Pisces is thought, by those in the astrology community, to mean a shift in focus. Pisces as a sign is associated with intuition, creativity, and compassion. Put them together, and – according to astrologists – you’ve got all the material to tout the beginnings of a new stage in your life; time to embrace that new creative endeavour, the business you’ve always dreamed of, or kickstart your new wellness regime.

But if you’ve got even a basic astronomy app installed on your phone, you’ll – quite understandably – be confused at these claims. A quick glance, and you’ll see that Saturn is not actually entering Pisces. In fact, astronomers from The University of Sussex, Liverpool John Moores University and BBC Sky at Night have categorically confirmed to BBC Science Focus that it’s set to remain in Aquarius until 2025.

"Saturn technically crosses the border from Aquarius to Pisces on 18 April 2025, an event which will have no bearing on the human race," explains astronomer and BBC Sky at Night presenter, Pete Lawrence.

So, what’s going on?

To answer this, we have to consider variables other than simply Saturn’s orbit. Yes – Saturn has a 29.4-year orbit. If we turn that into days (10,756 days) and divide that by 12, the number of zodiac constellations on the ecliptic, we get 896 days. Divide this by the number of days in a year (365), and we’ve got 2.5 (rounded up). So, according to this, Saturn stays in each constellation for 2.5 years, as it progresses through its 29.4-year orbit around the Sun.

So far, so good.

However, our view of the night sky is influenced by Earth's position, relative to what we’re viewing.

And there are other aspects at play.

Wibbly-wobbly, timey-wimey stuff

The Earth wobbles on its axis of rotation, like a toy spinning slightly off-centre. This slow wobbling motion causes a slight shift in the position of the stars and constellations in the night sky over time, an effect known as ‘axial precession’. This happens on a cycle of around 26,000 years.

In addition to changes in the distribution of solar radiation received by the Earth, precession is therefore pretty important when it comes to how we view the night sky, at our point in the geological timescale. And there’s also apsidal precession. Not only does Earth’s axis wobble, but Earth’s entire orbital ellipse also wobbles.

Astrologers, however, choose to ignore this crucial mechanism:

"Astrologists fail to take into account precession which, over time, causes the apparent position of the Sun to drift against the background stars," says Lawrence.

Due to precession, the position of the zodiac constellations have shifted over time; they’re not in the same place they used to be. And they will continue to move (and change shape) as the millennia go on.

More like this

Ignoring the effects of precession means that western astrologers use dates that are not representative of what is actually going on.

But it’s not just the position of the planets that western astrologers get wrong, as Dr Darren Baskill, astronomer and lecturer from the University of Sussex explains:

“The Sun does not move into the constellation of Pisces until the 12 March 2023, but astrologers say that the star sign of Pisces covers the period from 19 February – almost a month earlier.”

“The Sun moved in front of the constellation of Pisces on 19 February in the years around 700AD, so astrologers appear to be stuck 1,300 years in the past,” says Baskill.

By the same logic, we could argue that it’s still summer – when, at the time of writing, it is in fact a cold, drizzly day in March.

The zodiac band of sky

When the science of astronomy was still in its infancy, some of the first stars to be grouped into patterns, were those forming the background to the Sun as it moved across the sky, while the Earth in turn, was happily orbiting the Sun.

This narrow strip of sky is what we now know as the ‘zodiac band’. It’s centred on the ecliptic – the apparent path of the Sun across the celestial sphere – and extends approximately 9 degrees on either side. In other words, the zodiac constellations represent divisions of the sky along the ecliptic, and each constellation corresponds to an astrological sign: Aries, Taurus, Gemini, Cancer, Leo, Virgo, Libra, Scorpio, Sagittarius, Capricorn, Aquarius, and Pisces.

In astrology, it’s the position of the planets and stars within this band, that is believed to hold influence over personality traits, events, or human affairs.

So, why are astrologers saying that Saturn is entering Pisces, when it’s actually in Aquarius?

There’s a lot that popular media get wrong when it comes to astronomy. Aside from the sheer avalanche of articles regarding planets in constellations when they’re actually in another, remember how we discussed that the zodiac constellations represent divisions of the sky along the ecliptic?

For an astrologer, the ecliptic is divided into 30-degree ‘chunks’ (360 degrees divided by 12 zodiac constellations). Starting at 0 to 30 degrees (0 degrees being the location of the vernal equinox), we have the first star sign of the zodiac, Aries, then Taurus from 30 to 60 degrees – and so on.

But thanks to precession, these regions no longer contain the stars associated with their respective constellation. And to confuse matters further, a lot of astrologers incorrectly use these 30-degree regions of space, and their namesake constellations interchangeably.

2,000 years ago, this wasn’t an issue – the constellations were nestled in their respective regions. But it’s not so relevant today. And thanks to the cycle of precession, it’s going to be a long time before the constellations return home.

Pseudoscience or psychology?

While astronomy deals with the science, astrology is a divinatory system that seeks to interpret the supposed influence of celestial objects on human affairs and personalities.

In reality, there is no evidence that the position of the planets in relation to constellations, 30-degree bands of sky, or anything else in the celestial sphere, has any effect on our lives.

However, astrology has been practised for thousands of years and is still widely believed in by many people around the world. Some people find value in astrology as a form of self-discovery and personal reflection, and many people enjoy reading their horoscopes as a form of entertainment.

While the zodiac constellations have shifted over time, astrologers still use the traditional zodiac signs and meanings that were established thousands of years ago. The meanings and interpretations associated with each sign are based on ancient myths, symbolism, and tradition, rather than their actual astronomical positions.

Ultimately, whether astrology is ‘real’ or not depends on your perspective and beliefs. While there is no scientific evidence to support its claims, astrology can still have meaning and value for those who believe in it.

About our Experts

Pete Lawrence is an experienced astronomer and astrophotographer, and a presenter on BBC's The Sky at Night.

Dr Darren Baskill is an outreach officer and lecturer in the department of physics and astronomy at the University of Sussex. He previously lectured at the Royal Observatory Greenwich, where he also initiated the annual Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition.

Read more:

Authors

Sponsored Deals

May Half Price Sale

- Save up to 52% when you subscribe to BBC Science Focus Magazine.

- Risk - free offer! Cancel at any time when you subscribe via Direct Debit.

- FREE UK delivery.

- Stay up to date with the latest developments in the worlds of science and technology.