Zoology in 30 seconds: conservation and extinction

The book 30-Second Zoology, edited by Mark Fellowes, explains concepts about the natural world in bite-sized chunks. These three extracts begin with a biography of conservationist Patricia Wright, written by Rebecca Thomas.

There are many ways to become interested in science, but Patricia Wright’s journey is somewhat unusual. As a mother at home in Brooklyn, New York, in the 1960s, she owned two nocturnal owl monkeys.

She was fascinated by their behaviour and wanted to learn more about these primates in the wild; so, with her husband and daughter in tow, she embarked on an expedition to the jungles of Peru to study them. Nearly a decade later she received her doctorate before continuing her journey into conservation science.

Wright later set herself the challenge of trying to locate a species that many considered to be extinct. She travelled to Madagascar, a country filled with endemic species, on the hunt for the greater bamboo lemur. She not only rediscovered the greater bamboo lemur but she also found another new to science, the golden bamboo lemur.

As amazing as these discoveries were, Wright was shocked by the devastation she saw around her. Madagascar had already lost so much of its natural habitat, but with logging threatening the survival of these bamboo lemurs as well as many other animals, she knew she must act.

Read more about ecology:

- 14 amazing photos from the BMC Ecology Image Competition 2018

- How we can save the oceans, and how they can save us

Collaborating with local people and the Madagascan government, Wright worked to gain support and raise funds to set up the Ranomafana National Park. In return for not exploiting the resources in the forests, local people were provided with schools and healthcare facilities as well as new employment opportunities within the park. The park now receives over 100,000 visitors each year, bringing much-needed money into the local economy.

More like this

With this incredible area given formal protection, Wright set about establishing Centre ValBio, a research facility positioned next to Ranomafana National Park. The centre has enabled exciting research to be carried out throughout Madagascar, but it is also committed to reducing poverty in the local area to allow for sustainable use of natural resources. With local conservation clubs and the establishment of ecotourism in the region, the local people are gaining an understanding of the value of conservation.

Patricia Wright’s conservation message is also being felt at an international level. Each year Centre ValBio welcomes students from across the world in Study Abroad programmes, and Patricia herself and the research being carried out at the centre have been showcased in numerous media outlets, including the 2014 film Island of Lemurs: Madagascar.

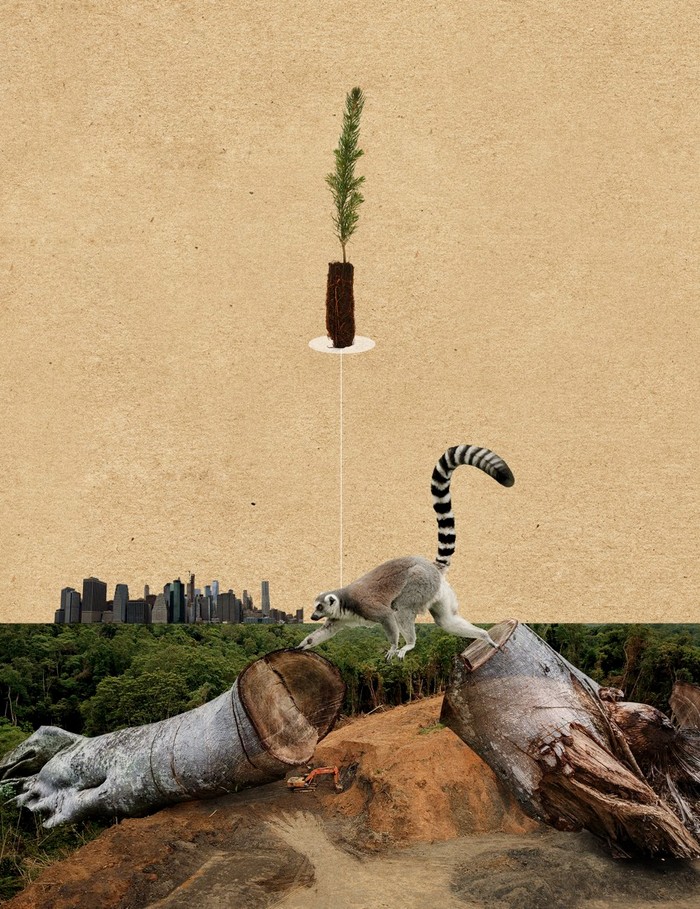

Habitat Loss

Loss of native habitat directly affects a species’ ability to survive through increased competition for declining resources, from food to places to hide.

Humans are transforming vast swathes of our planet’s surface at a pace unlike any other seen in recent geological time, and habitats are being altered so dramatically that habitat loss is now the greatest cause of global species extinction. Throughout human history we have changed the land, mostly for small-scale agriculture, but more recently we have created vast mega-cities and industrial-scale agriculture so that today over half of the Earth’s land surface is no longer natural.

This has been driven by rapid human population growth and the resulting increase in demand for food and consumer goods, pushing many species to the brink of extinction. Forests, the most biodiverse habitats, have been the worst affected by this devastation. In Madagascar, for example, nearly 90 per cent of native forest cover has been lost, threatening many lemur species.

Lemurs are found only here, and with the human population increasing, the lemurs’ survival relies on preserving natural habitats. Even ring-tailed lemurs, one of the most widely recognised species, is threatened through habitat destruction. Ring-tailed lemurs breed well in captivity, and they are very adaptable, so reintroduction programmes are possible in areas where they have been lost – but success in this is dependent on them having a habitat to return to.

Human-wildlife conflict

Sharing the planet with other species requires strategies that promote mutual harmony and sustainable solutions.

For many, a connection with nature is part of what makes life special and memorable. For these people, contact with wildlife is seen as a boon; holidays are focused on natural areas, wildlife documentaries are enjoyed and, even on our doorsteps, providing food for garden birds and other wildlife is something many people do.

Read more about conservation:

- Conservation: How China is creating Edens

- Endangered orangutan numbers starting to stabilise thanks to conservation efforts

- Northern white rhino embryo could save all-female subspecies from extinction

But when humans and wildlife mix, conflicts can arise, with wild animals seen as a threat to livelihoods, health and well-being. For those who rely on agriculture, crop losses mean financial losses, and human–wildlife conflicts around farming can be devastating.

Elephants epitomise this duality. For ecotourists, elephants are one of the most charismatic of mega-fauna, a species worth travelling around the world to see in the wild. But elephants can also cause extensive damage when raiding agricultural areas to find food, causing damage by trampling crops while moving through the fields.

This can have serious consequences for the local human communities, and as a result persecution does take place. But working with local knowledge is often the best method for reducing conflict. Elephants do not like plants containing capsaicin, and they also have an aversion to bees, so farmers use chilli-plant fences and beehives to deter them.

Sponsored Deals

May Half Price Sale

- Save up to 52% when you subscribe to BBC Science Focus Magazine.

- Risk - free offer! Cancel at any time when you subscribe via Direct Debit.

- FREE UK delivery.

- Stay up to date with the latest developments in the worlds of science and technology.