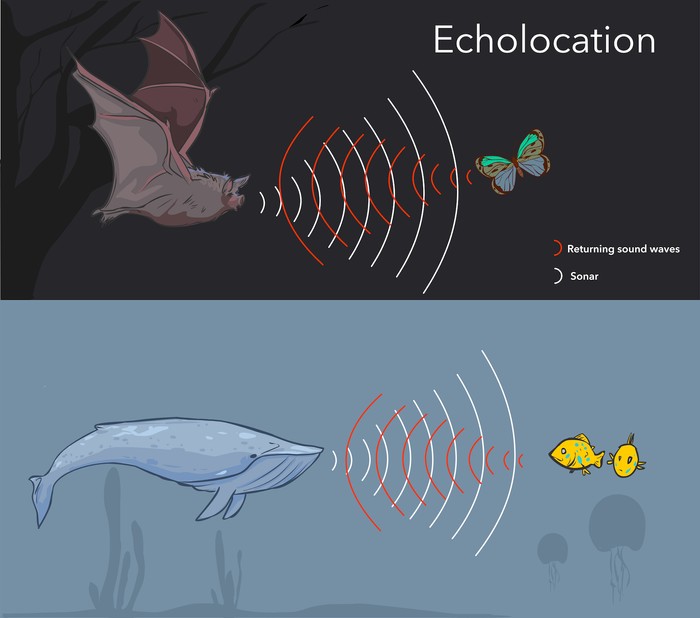

How does echolocation work?

With its built-in sonar, honed through millions of years of evolution, the bat is the undisputed poster child of echolocation.

This furry, flying critter shouts into the void, and then listens to the echoes that bounce back from objects in the darkness. Echolocation helps the bat to navigate, and to chase and snatch prey, such as moths, straight out of the sky.

Most of the world’s 1,400 bat species use echolocation. They produce pulses of sound, largely in the ultrasound range, high above the limits of human hearing. Most bats contract their larynx muscles to make the clicks via an open mouth, but some species use other body parts. Leaf-nosed bats make calls through their elaborate noses, while some fruit bats make clicks by flapping their wings.

As the bat closes in on its prey, the pulses increase in frequency to more than 160 clicks per second. The returning echoes then help the bat to determine the size, shape, texture, distance and direction of the prey or object. At up to 140 decibels, the shrieks are also incredibly loud. Just before it calls, the bat contracts its middle ear muscle, effectively dialling down its hearing, so the mammal is not deafened by its own cries. The situation is then reversed almost instantly, so the echoes can be detected.

Toothed whales, including dolphins and porpoises, also echolocate, as do certain birds and small mammals, such as some tenrecs and shrews. The strategy makes sense for species that are active at night, or that live underground or deep in the ocean, where visual cues are limited.

Read more:

- Would it be possible for driverless cars to use echolocation?

- If bats are blind, why do they have eyes?

- How does human noise affect ocean life?

- Why are there so many species of bat?

Asked by: Ella McGregor, Edinburgh

To submit your questions email us at questions@sciencefocus.com (don't forget to include your name and location)

Authors

Sponsored Deals

May Half Price Sale

- Save up to 52% when you subscribe to BBC Science Focus Magazine.

- Risk - free offer! Cancel at any time when you subscribe via Direct Debit.

- FREE UK delivery.

- Stay up to date with the latest developments in the worlds of science and technology.